Updated high-level analysis of the Irish grocery retail sector – August 2025

Introduction

Irish consumers are currently experiencing a sharp increase in grocery prices[1], a trend that is affecting consumers across the globe in recent years. This has significantly contributed to the cost-of-living pressures faced by consumers and has sparked widespread public commentary on the underlying reasons for these increases.

In 2023, the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (CCPC) carried out a high-level analysis of competition in the Irish grocery retail sector.

This analysis[2] found no indications of market failure or excessive pricing due to abuse of dominance, noting that competition had improved in recent years with more choice for consumers and increased entry by retailers. While food prices in Ireland remained high internationally, food inflation during the period analysed had been the lowest in the EU, and available data did not suggest unusually high profit margins among retailers.

Given the ongoing conversations around grocery price increases and the continued pressures faced by consumers in this space, we have carried out an updated analysis of how the market is functioning and whether there are indications that interventions may be necessary to address potential market failures.

In updating our 2023 work, we have applied standard market analysis tools to produce a high-level analysis of the grocery retail sector, which allows us to identify indications of potential market failures. Our analysis includes reviews of:

- market concentration and entry/expansion

- national and international trends in grocery prices

- profit margins of major grocery retailers

We have also provided a review on wider issues in the grocery retail sector which fall within the CCPC’s remit.

High-level analysis of competition in the grocery retail sector in Ireland

The grocery retail sector includes supermarkets, convenience stores and specialist food stores. The five main nationwide supermarket chains in Ireland – Dunnes Stores, Tesco, SuperValu, Lidl, and Aldi – account for approximately 93% of the market. While this is up from 91% in our 2023 analysis, this figure fluctuates on a monthly basis[3].

Although competition in the grocery retail sector generally occurs at the local level, operational decisions such as pricing are typically uniform and apply nationwide. Therefore, national market share provides an appropriate framework for assessing the level of concentration within this sector.

Concentration

In order to consider whether there might be fundamental competition issues within a particular sector, one key indicator is market concentration, which provides a snapshot of market structure. Where a market is highly concentrated with few players competing against each other, this might be an indication that price competition is not strong, and traders may have the power to increase prices without the fear that competitors will react and take significant customer share away from them.

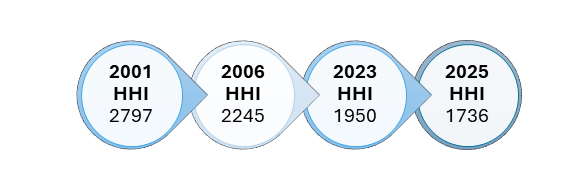

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is a measure of industry competitiveness in terms of market concentration among its participants. Higher index values indicate greater market concentration, potentially greater market power and lower competition. A market with a HHI of less than 1,500 is considered competitive, a HHI between 1,500 and 2,500 shows moderate levels of competition and concentration, and a HHI above 2,500 is highly concentrated.

The national market shares of major grocery retailers, based on consumer receipts survey data and as reported by Kantar in June 2025, are as follows: Dunnes Stores (23.6%), Tesco (23.3%), SuperValu (20.2%), Lidl (14%), and Aldi (11.8%).

To better understand the significant changes in competition since 2001, we have used the number of retail stores nationally to provide a measure of how market shares have changed[4]. Based on these figures, the HHI is 1,736 as of May 2025. This shows the market has become significantly less concentrated over time and this trend has continued since 2023. (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Market concentration HHI (based on number of retail units)

This indicator suggests that competition has increased over the period as a larger number of stores from a larger number of competitors are now competing for customers across the country.[5]

Entry and expansion

Another key indicator of a healthy market is one where competitors can demonstrate an ability to enter and expand. Our 2023 analysis highlighted the entry of Lidl and Aldi as having a significant impact on competition in the market. We note that no other major European grocery retailers have entered the market in recent years.

Since 2023, the main grocery retailers in Ireland have expanded their presence, opening approximately 29[6] new stores across the country. This growth trajectory is set to continue, with Aldi announcing in June 2024 its plans to open 30 new stores by 2030[7], and Lidl revealing in February 2025 its intentions to open 35 new stores within the same period.[8] Additionally, Tesco has committed to opening 10 new stores over the next 12 months, as announced in July 2025.[9]

Competitive dynamics

The dynamics in the grocery retail sector and how companies compete with one another is an important indicator for a market analysis. A healthy market is more likely to see companies appeal to consumers through aggressively offering better prices and services. It is also more likely to see companies compete by operating slightly different business models to gain a competitive advantage and innovating to attract consumers. The dynamics we identified in 2023 are still relevant, and we continue to see aggressive price competition, new loyalty card schemes and different product offerings.

The business focus on own-brand products has continued to grow, with recent data showing a shift in market value share. In July 2025, Kantar reported that own brand had overtaken brands with a total value share at 47.3%, compared to brands with a 47.1% value share.[10]

Overall, the grocery retail sector demonstrates positive signs of competitive dynamics with new products and services and a strong level of competition on price including aggressive marketing to consumers on price offers.

Food price inflation: Ireland and internationally

Examining inflation in a particular sector, such as groceries, can provide important evidence on how the market itself is functioning. If a market is not functioning well, it often means companies with significant market power can increase prices substantially above a competitive level. One approach to analyse this is to consider whether prices are being increased over and above comparable international price increases.

The most definitive assessments of price developments over time in Ireland and internationally are the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is the official measure of inflation for Ireland, and the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), which is the European equivalent of the CPI that follows the same methodology as the CPI. The HICP allows us to carry out the most robust comparison of international price trends.

The recent rise in grocery prices has resulted in a considerable amount of concern and commentary including questions on whether the increases facing Irish consumers are driven by the lack of competition amongst Irish supermarkets.

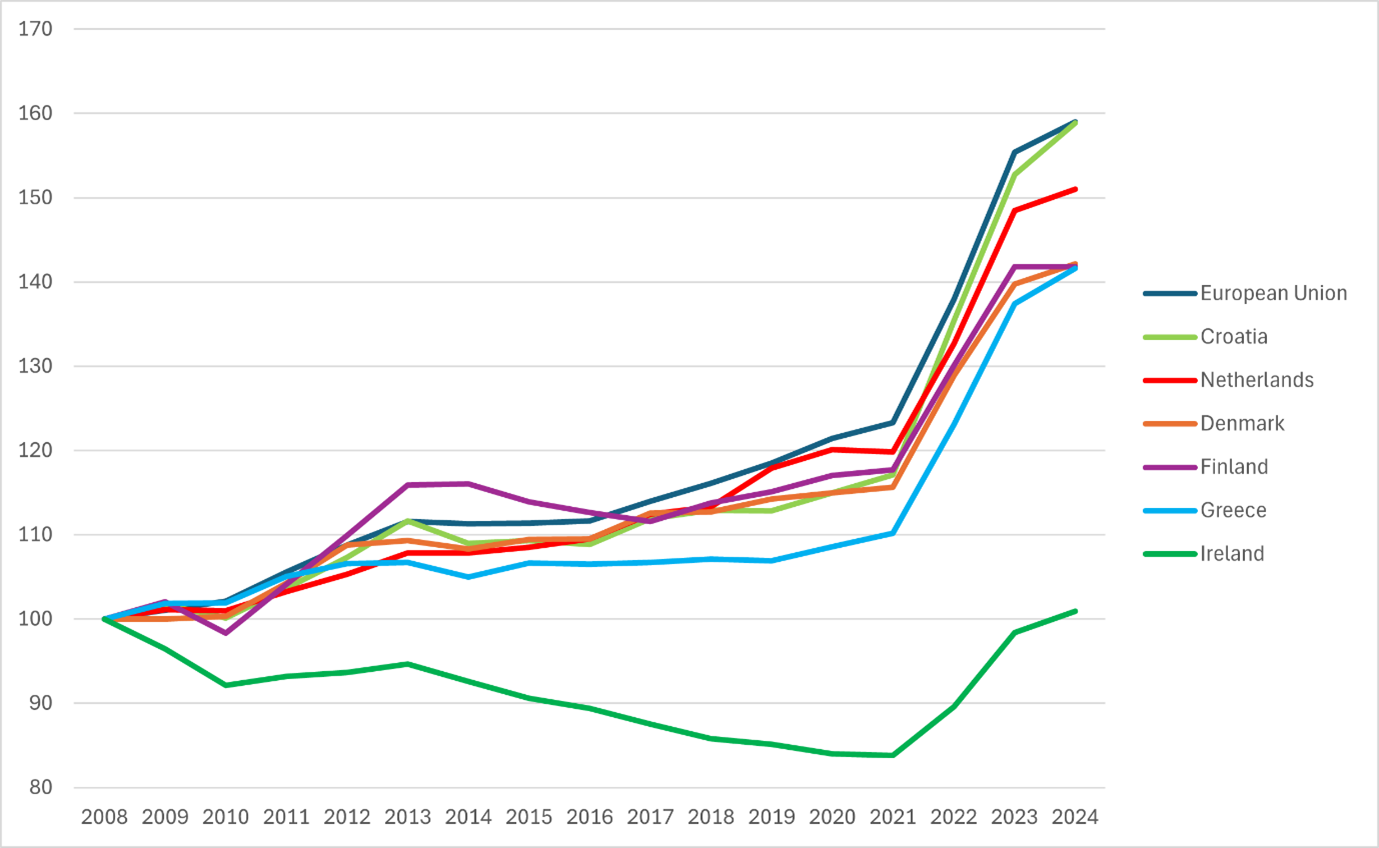

Before examining more recent trends in grocery price inflation, it is worth considering how prices have developed over time in Figure 2 (below). Ireland’s rate of grocery price inflation has been below the EU average for 15 of the past 16 years (every year since the 2008 financial crisis apart from 2024).

Figure 2: Harmonised Index of Consumer Grocery Prices (Food and non-alcoholic beverages) (2008=100) multiple countries

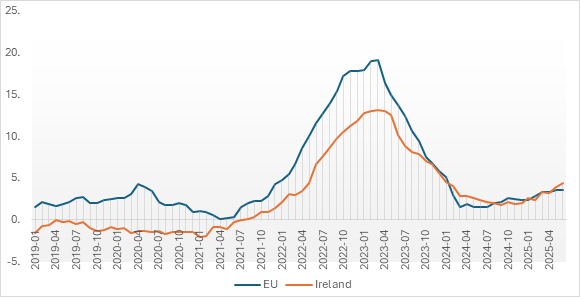

Figure 3 (below) provides a more focused view on recent years showing more clearly the large recent increases in grocery prices. It shows significant upward pressure on grocery prices since 2021, where Irish consumers have experienced a 27% increase in prices up to June 2025. While significant, this rise remains below the EU average where grocery prices have increased by 35% over the same period. Only four other EU member states have experienced smaller price increases since 2021. It also further highlights that grocery inflation in Ireland has mostly been lower than the EU in recent years, with EU and Irish inflation rates in close alignment since 2024.

Figure 3: Harmonised Index of Consumer Grocery Prices (% change m/m-12) EU vs Ireland

Separate to the CPI and the HICP, the Central Statistics Office (CSO) recently published ‘Price Levels of Food, Beverages, and Tobacco 2024: How Ireland Compares’, showing Ireland’s[11] price levels higher relative to other EU countries.

The most recent estimates from the CSO for 2024 place Irish retail grocery prices as being 14% higher than the EU average.[12] This gap has reduced since 2003[13] when Irish prices were 30% higher. While the 14% figure raises potential questions about competition in the market for groceries, it must be considered in the context of a number of structural factors at play in the Irish economy, including higher wages[14], remote geographic location and higher costs in sectors such as construction, legal services and insurance which are likely to apply upward pressure on prices in Ireland.

Overall, the high-level inflation figures do not suggest any significant market problems in the Irish grocery retail sector. If anything, the evidence suggests that Irish consumers have experienced significant price benefits compared to European counterparts. There is a strong argument to suggest that this benefit has been influenced by the increased competition in the grocery retail sector discussed above.

Wider supply chain

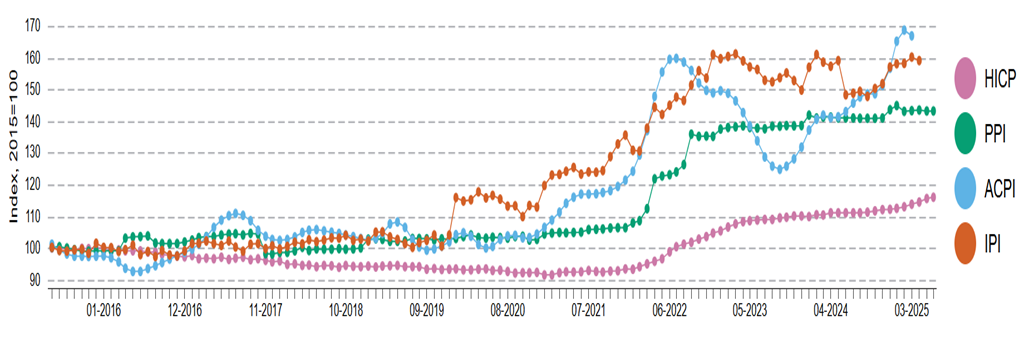

[15] When analysing retail inflation[16] – particularly in the context of groceries – it’s important to also consider the broader pricing chain, including import costs[17], producer prices[18] and agricultural prices[19]. These three figures give a good indication of the costs faced by retailers. By analysing them alongside the prices consumers pay (HICP) we can understand how grocery stores react when their costs change. Do their prices increase in line with their costs?

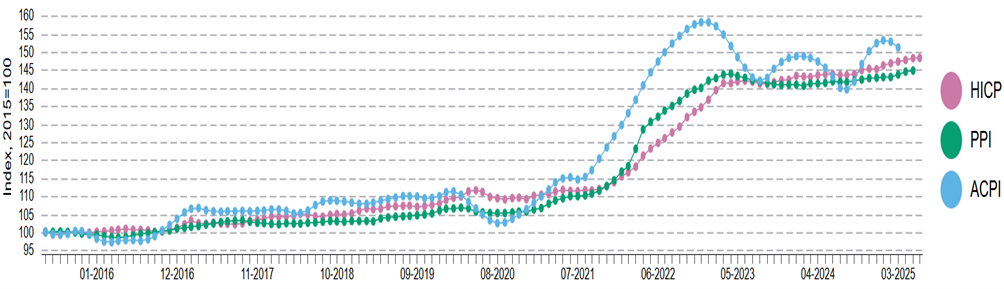

As illustrated in Figure 4 (below), Ireland has experienced significant cumulative price increases since 2019 in import prices, agricultural commodity prices[20] and producer prices, but retail prices (HICP) have increased at a much slower pace.

Figure 4: Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), Producer Price Index (PPI), Agricultural Commodity Price Index (ACPI) and Import Price Index (IPI) June 2015 – June 2025 – Food (Index) Ireland

Source: Eurostat

This may indicate that retailers are absorbing some of the cost pressures rather than passing them fully on to Irish consumers. A lower pass-through suggests strong competition in the supply chain. This pattern is not reflected in the EU data shown in Figure 5 (below) where increases in the retail price of food have tended to more closely follow agricultural and producer prices.

Figure 5: HICP, PPI, and ACPI June 2015 – June 2025 – Food (Index) EU

Source: Eurostat

Product focus

Given recent increases in grocery inflation in Ireland, it is worth examining inflation at a product level to understand the underlying drivers.

Table 1: Annual rate of inflation at product level, Jan-June 2025 average

| Inflation Rates | Ireland | EU | UK |

| Food & Non-alcoholic Beverages | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.7 |

| Basket of Goods | |||

| Bread & Cereals | 2.3 | 1.7 | 3.2 |

| Meat | 4.2 | 2.8 | 3.4 |

| Fish | 1.9 | 2 | -1.1 |

| Milk, Cheese, Eggs | 5.4 | 3.7 | 2.7 |

| Oils and Fats | 6.1 | -1.9 | 7 |

| Fruit | 1.1 | 5.4 | 3.6 |

| Sugar, Jam, Syrup, Confectionary | 7.5 | 6.5 | 8.6 |

| Vegetables | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2 |

| Baby Food | -0.8 | 1.1 | Not Available |

Based on Eurostat HCIP and UK CPI data

The table above shows the average inflation rates for various product categories over the first half of 2025. Inflation rates across the basket of goods varies, with Ireland having a lower rate of inflation in three out of the nine categories when compared to EU and five out of nine when compared to the UK.

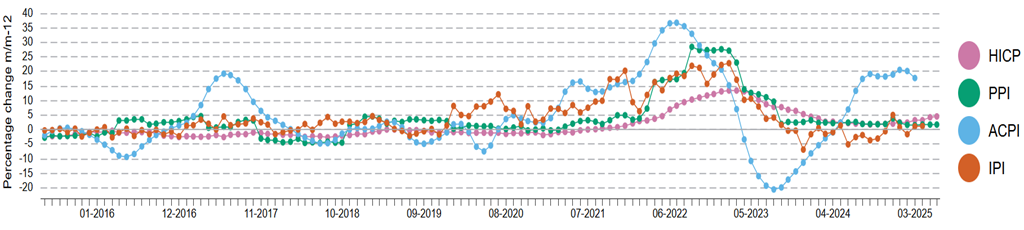

Given that the growth at product-level inflation is more pronounced in the area of some agricultural products[21], it is beneficial to consider the year-on-year percentage change shown in Figure 6 (below) across the various supply chain prices to better understand recent inflation trends in Ireland.

Figure 6: HICP, PPI, ACPI and IPI 2015 – 2025 – Food (% change m/m-12) Ireland

Source: Eurostat

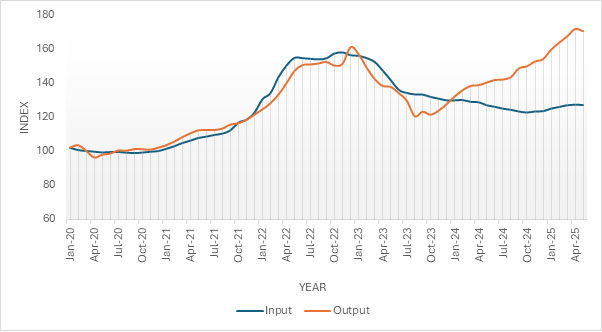

As seen in Figure 6, agricultural prices exhibit the most volatility from 2022 onwards. To better understand what might be driving these changes in agricultural prices we have set out a breakdown of agricultural input prices which includes items such as fertilisers, pesticides, feed, seed, energy and lubricants, maintenance and repairs, etc., and agricultural output prices, i.e. the price received by farmers from processors/retailers for products such as milk, eggs, livestock, etc. in Figure 7 (below).

Figure 7: Agricultural input and output price levels Ireland: January 2020 to April 2025

We can see that up until 2024, agricultural output prices largely tracked agricultural input prices. But in the very recent period, agricultural output prices have shown a strong increase compared to agricultural input prices. Between Q1 2024 and Q1 2025, agricultural output prices (which are input prices for processing or grocery retail stores) in Ireland rose by 19.3% – the highest in the EU and significantly above the EU average of 2.6% for the same period.[22] These recent trends are in contrast to the 2020-2023 period where agricultural output prices were in closer alignment with agricultural input prices.

Between Q1 2024 and Q1 2025, agricultural input prices in Ireland actually fell by 4.6%, the second-highest decline in the EU, just behind Lithuania (-5.9%).[23]

In summary, while Irish grocery retail prices have increased since 2021, they have done so at a slower pace compared to import, agricultural and producer prices, indicating that competitive pressures in the retail grocery market may be preventing the full extent of price increases along the supply chain being passed on to consumers.

While the data points to upward pressures in agricultural output prices as being an underlying factor in recent grocery inflation, this observation relates to a short period of time (2024-2025). The recent increase in Irish agricultural output prices is likely to be driven by a combination of factors along the supply chain such as increased global demand, supply constraints and global market volatility.

The CCPC notes that price development along the food supply chain, including buyer power and margins, is part of the role for An Rialálaí Agraibhia (Agri-Food Regulator) focusing on the promotion of fairness and transparency. An Rialálaí Agraibhia has two functions in this regard: a price and market analysis and reporting function, and a regulatory enforcement function concerning the enforcement of prohibited unfair trading practices.

Profitability

Profit margins can provide useful evidence in a market analysis. It is important to emphasise that profit margins can differ from industry to industry for a range of reasons. Traders who have different business models with different risk profiles will have different profit levels.

We have continued to review public financial accounts of supermarkets since publication of our high-level analysis in 2023 (i.e. Tesco[24], Aldi, Musgrave).[25] Recent results continue to be in line with the margin band estimated by the CCPC in 2023 (1%-4%) e.g. Tesco Ireland’s operating profit margin for the year to Feb 2024 was 3.7%[26], down from 4% in previous year; Musgrave’s profit margin in 2023 was 2.4%, down from 2.5%; Aldi’s profit margin in 2023 was 0.8%, down from 0.9% in 2022. Thus, all three groups have reported declining profitability (albeit marginal) in their latest financial results. Dunnes and Lidl do not publish accounts for their Irish operations, however Lidl’s UK accounts (which combine UK and Irish activities) for 2023/2024 show a profit margin of 2.1%.

The profit margins for Irish supermarkets align closely with those observed in the UK and other parts of Europe. For instance, both Sainsbury’s and Asda reported profit margins of approximately 3% for the 2023/24 period. In Denmark, the Salling Group achieved a margin of 3.7% in 2024, while the largest supermarket chain in the Netherlands reported a margin of 4%.

These margins are notably lower than those of some producers within the market. For example, Unilever reported a margin of 18.4% in 2024, up from 16.7% in 2023. Similarly, Kerry Group maintained a margin of 11.2% in 2024, a slight decrease from 11.3% in 2023. Glanbia also showed strong performance with a margin of 14.4% in 2024, up from 13.6% the previous year. As noted above, caution is needed when looking at a single year and making direct comparisons across different businesses.

Role of the CCPC in relation to the grocery sector

The CCPC has a role in relation to enforcing the relevant law on pricing and price display, through a number of legal instruments including the Consumer Protection Act 2007, the Consumer Rights Act 2022 and the European Communities (Requirements to Indicate Product Prices) Regulations 2002. Irish consumer protection laws on pricing oblige traders to clearly display prices to consumers before they make a transaction. If a trader charges a price for a product which is higher than the displayed price, this may constitute a misleading commercial practice. The regulations introduced in 2022 aim to end the practice of raising selling prices immediately prior to a sale in order to advertise misleadingly large discounts. Any business advertising a discount is now required to display the previous price, which must be the lowest price applied in the previous 30 days.

The CCPC brought a prosecution against Tesco for failure to display unit pricing on Clubcard price labels. On 24 June 2024, Tesco Ireland Limited entered guilty pleas in the Dublin Metropolitan District Court in respect of two summonses. The judge applied the Probation Act and ordered the trader to pay the legal costs of the CCPC and a donation of €1,000 to the Little Flower Penny Dinners charity.

In the context of the CCPC’s statutory functions in competition, our investigation and enforcement functions are set out under section 10 of the Competition and Consumer Protection Act 2014. Of specific relevance, the CCPC can prohibit or remedy mergers or acquisitions that are likely to result in a substantial lessening of competition. For example, the CCPC protected consumers in Galway from a damaging increase in concentration in the grocery sector through its merger review of a proposed supermarket acquisition by Tesco. The CCPC approved the deal in 2022 only after Tesco agreed to divest an outlet in Oranmore to Musgrave and the store now offers additional competition and convenience to consumers.

Conclusion

Our update to the 2023 high-level analysis of the grocery retail sector reviewed market concentration, national and international trends in grocery prices and wider issues in the grocery sector, which fall within our remit. Through this work, we have found that:

- Overall, there is no evidence indicating that competition is not working in the Irish grocery retail sector.

- The increased competition in the market over the last 20 years has brought sizeable benefits for consumers. Food price increases in Ireland have been well below the European average, and this coincides with increasing competition in the Irish market.

- The data available on profit margins does not indicate that margins are notably high when compared to international comparators.

- Inflation analysis shows significant price increases since 2021 that have a real impact on consumers both in Ireland and across Europe.

- One key driver of recent food price rises is the increase of some agricultural product prices, which have been higher in Ireland than the European average.

- While grocery prices have increased significantly since 2021, they have done so at a slower pace than some of the key input costs, such as agricultural prices. This suggests that competition in the grocery market has helped limit the impact of increased agricultural prices on Irish consumers.

The CCPC will continue to focus its in-depth work on sectors where there is some evidence of potential market failures and where we believe the work will deliver significant benefits to consumers. For example, we have made recommendations in relation to the legal, home and car buying, and waste sectors, which would allow markets to function better and have a real impact for consumers. While the CCPC has not seen evidence to justify an in-depth study of the grocery retail sector, it remains a key market for the CCPC, which we will continue to review.

Footnotes

[1] The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by 1.8% between June 2024 and June 2025, up from an annual increase of 1.7% in the 12 months to May 2025. Food and non-alcoholic beverages rose by 4.6% in the same period. Food and non-alcoholic beverage prices are referred to as grocery prices from this point on unless otherwise stated.

[2] For more detail, see: https://www.ccpc.ie/business/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2023/06/2023.06.16-CCPC-Competition-Analysis-Retail-Grocery-Sector.pdf

[3] Based on Kantar data as of June 2025: https://www.kantarworldpanel.com/ie/grocery-market-share/ireland

[4] Kantar data has only been available since 2014. To better understand the significant changes in competition since 2001, particularly with the entry of Aldi and Lidl, the number of retail stores nationally offers a more useful measure of market shares.

[5] This trend is not necessarily apparent elsewhere. For instance, recent studies in Australia and New Zealand pointed to highly concentrated grocery sectors in which competition was not working well for consumers. See: Supermarkets inquiry 2024-25 | ACCC and Commerce Commission – Market study into the grocery sector.

[6] This number also includes Tesco express stores. It does not include Marks and Spencer’s “Shop-in-Shop” expansion in collaboration with Applegreen.

[7] See, https://www.retailnews.ie/news-and-views/aldi-to-invest–400-million-in-new-stores-and-jobs-over-next-five-years/

[8] See: https://www.rte.ie/news/business/2025/0213/1496498-lidl-600m-investment-plans-for-35-new-stores-and-rdc/

[9] See: https://tescoireland.ie/tesco-announces-400-new-jobs-with-40-million-investment-in-new-stores/

[10] For more information see: Early Summer spending boosts Irish grocery market by an extra €29 million.

[11] In 2024, food and non-alcoholic beverages in Ireland were 14% higher than the EU average. See: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cpl/pricelevelsoffoodbeveragesandtobacco2024howirelandcompares/

[12] The CSO comparative price level publication should be interpreted with caution as the Central Statistics Office noted in its 2021 release that, “the Consumer Price Index is a more reliable measure of the development of prices in a given country. Similarly, if we want to compare the rate of price change in two or more countries the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) is readily available, at least for European Countries”. The CSO also notes that the main use of the methodology underpinning the price level comparisons in the Eurostat / CSO release is to convert national accounts aggregates, like the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of different countries, into comparable volume aggregates. The CSO advises that while it can also be applied in the analysis of relative price levels across countries, it is not designed for cost-of-living comparisons for individuals.

[13] Data prior to 2003 is not available. See, [prc_ppp_ind] Purchasing power parities (PPPs), price level indices and real expenditures for ESA 2010 aggregates. We also note that the estimated improvement in Ireland’s price level position relative to the EUis not as large as is implied by the trends in their respective HICPs – another reason for caution in the interpretation of the comparative price level indices.

[14] In 2024, hourly wages and salaries in Ireland were 40% higher than the EU average. See: [lc_lci_lev] Labour cost levels by NACE Rev. 2 activity

[15] Grocery prices in this section refers to ‘food’ and not ‘food and non-alcoholic beverages’

[16] Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), is the European equivalent of the CPI and is readily available for international comparisons.

[17] Import Price Index measures the price of imported goods and helps identify external drivers of inflation (e.g. rising energy prices). This is an important indicator when considering prices in Ireland as we are heavily reliant on imported food and agricultural inputs, and as such our prices are sensitive to global commodity markets.

[18] Producer price index measures price changes of goods sold by manufacturers, reflecting cost pressures at the production level – often a leading indicator of consumer inflation.

[19] The ACP monitors raw food commodity prices (e.g. dairy, livestock), and spikes in these agricultural prices can impact both the PPI and HICP.

[20] With the exception of the period July 2022-Sept 2023.

[21] Changes in inflation relating to oil & fats and sugar, jam etc. are more generally influenced by international factors due to our heavy reliance on imports in these categories.

[22] Based on data extracted from Eurostat: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/apri_pi20_outq__custom_17473732/default/table?lang=en.

[23] Based on Eurostat data: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/apri_pi20_inq__custom_17473723/default/table?lang=en

[24] Tesco Ireland started to publish accounts for its Irish operations following publication of our analysis in 2023. Prior to this Irish figure were combined with UK figures.

[25] Dunnes Stores does not publish accounts; Lidl combines Irish data with European data.

[26] Tesco’s UK and Irish operations combined was 4.2%